reading_notes

Read: Class 11 - Authentication:

What is OAuth?

OAuth is an open-standard authorization protocol or framework that describes how unrelated servers and services can safely allow authenticated access to their assets without actually sharing the initial, related, single logon credential. In authentication parlance, this is known as secure, third-party, user-agent, delegated authorization.

Give an example of what using OAuth would look like.

The simplest example of OAuth is when you go to log onto a website and it offers one or more opportunities to log on using another website’s/service’s logon. You then click on the button linked to the other website, the other website authenticates you, and the website you were originally connecting to logs you on itself afterward using permission gained from the second website.

How does OAuth work? What are the steps that it takes to authenticate the user?

Let’s assume a user has already signed into one website or service (OAuth only works using HTTPS). The user then initiates a feature/transaction that needs to access another unrelated site or service. The following happens (greatly simplified):

The first website connects to the second website on behalf of the user, using OAuth, providing the user’s verified identity. The second site generates a one-time token and a one-time secret unique to the transaction and parties involved. The first site gives this token and secret to the initiating user’s client software. The client’s software presents the request token and secret to their authorization provider (which may or may not be the second site). If not already authenticated to the authorization provider, the client may be asked to authenticate. After authentication, the client is asked to approve the authorization transaction to the second website. The user approves (or their software silently approves) a particular transaction type at the first website. The user is given an approved access token (notice it’s no longer a request token). The user gives the approved access token to the first website. The first website gives the access token to the second website as proof of authentication on behalf of the user. The second website lets the first website access their site on behalf of the user. The user sees a successfully completed transaction occurring.

What is OpenID?

OpenID is about authentication, for humans logging into machines, in 2005 the idea was that rather than having multiple logins for multiple websites, OpenID would serve as a single sign-in, vouching for the identities of users, By 2011, OpenID had become an also-ran, and, Wired declared that “The main reason no one uses OpenID is because Facebook Connect does the same thing and does it better. OpenID remains a difficult task, which means that while thousands of websites support it, hardly anyone uses OpenID. OpenID promised to solve two problems. First, it would offer an easy way to log in to any website without needing to create a new account. And, second, it would enable you to have a consistent identity across the entire web. This worked well with the limited audience of bloggers and tech-savvy users that were part of the original vision.

Authorization and Authentication flows

What is the difference between authorization and authentication?

Auth0 uses the OpenID Connect (OIDC) Protocol and OAuth 2.0 Authorization Framework to authenticate users and get their authorization to access protected resources. With Auth0, you can easily support different flows in your own applications and APIs without worrying about OIDC/OAuth 2.0 specifications or other technical aspects of authentication and authorization.

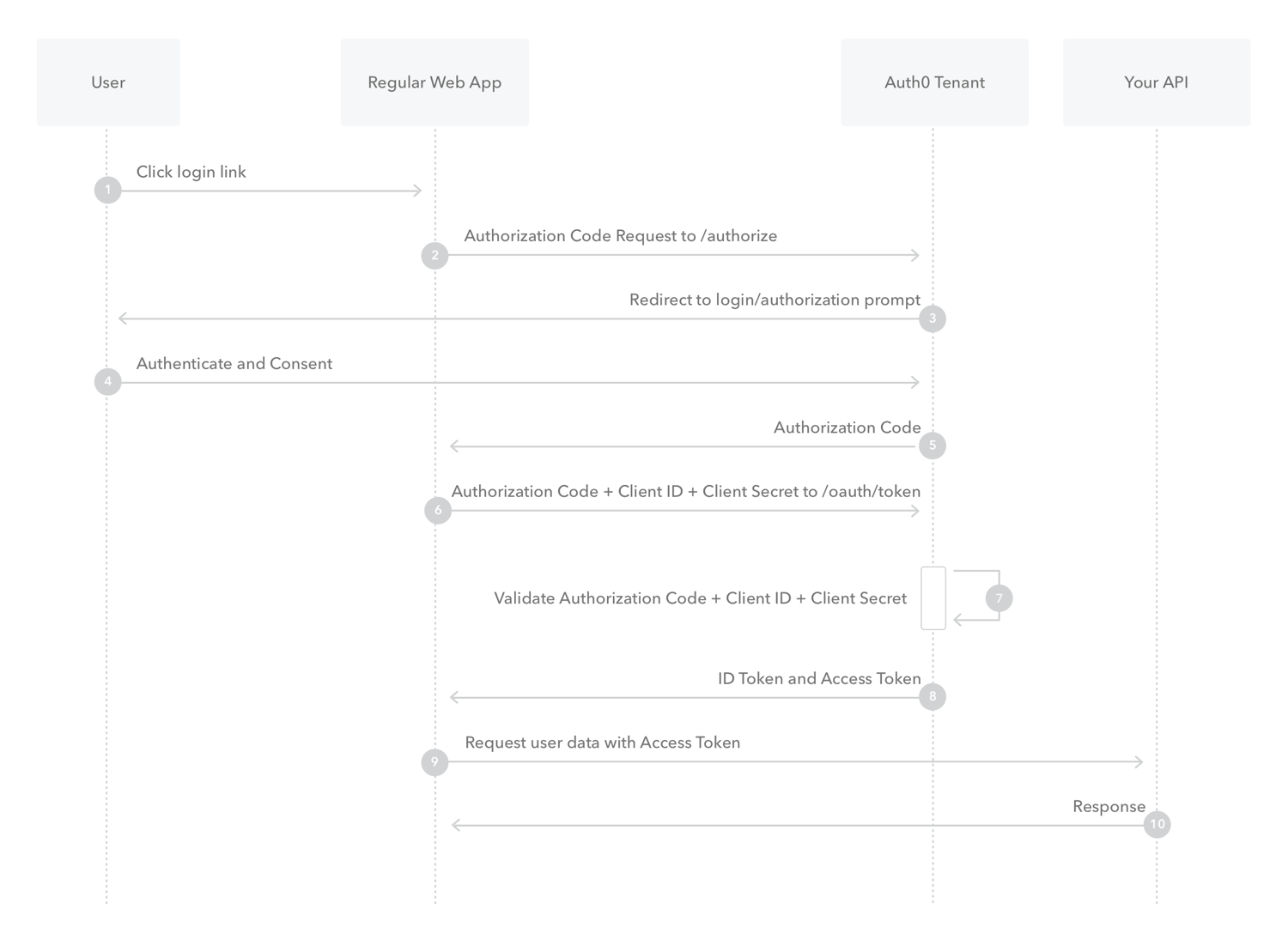

What is Authorization Code Flow?

Because regular web apps are server-side apps where the source code is not publicly exposed, they can use the Authorization Code Flow, which exchanges an Authorization Code for a token. Your app must be server-side because during this exchange, you must also pass along your application’s Client Secret, which must always be kept secure, and you will have to store it in your client.

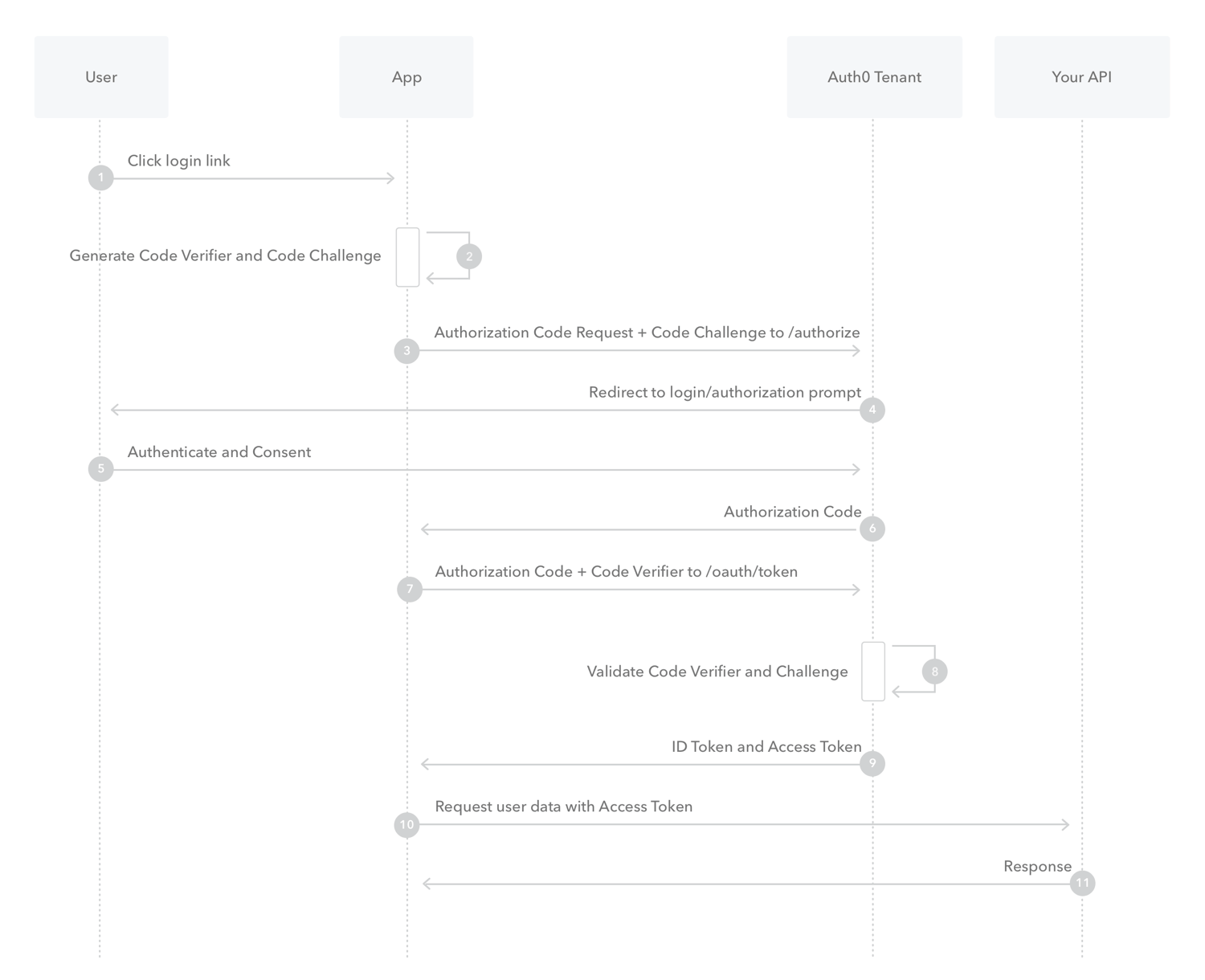

What is Authorization Code Flow with Proof Key for Code Exchange (PKCE)?

When public clients (native and single-page applications) request Access Tokens, some additional security concerns are posed that are not mitigated by the Authorization Code Flow alone.

The PKCE-enhanced Authorization Code Flow introduces a secret created by the calling application that can be verified by the authorization server; this secret is called the Code Verifier. Additionally, the calling app creates a transform value of the Code Verifier called the Code Challenge and sends this value over HTTPS to retrieve an Authorization Code. This way, a malicious attacker can only intercept the Authorization Code, and they cannot exchange it for a token without the Code Verifier.

What is Implicit Flow with Form Post?

Implicit Flow with Form Post flow uses OIDC to implement web sign-in that is very similar to the way SAML and WS-Federation operates. The web app requests and obtains tokens through the front channel, without the need for secrets or extra backend calls. With this method, you don’t need to obtain, maintain, use, and protect a secret in your application.

What is Client Credentials Flow?

With machine-to-machine (M2M) applications, such as CLIs, daemons, or services running on your back-end, the system authenticates and authorizes the app rather than a user. For this scenario, typical authentication schemes like username + password or social logins don’t make sense. Instead, M2M apps use the Client Credentials Flow, in which they pass along their Client ID and Client Secret to authenticate themselves and get a token.

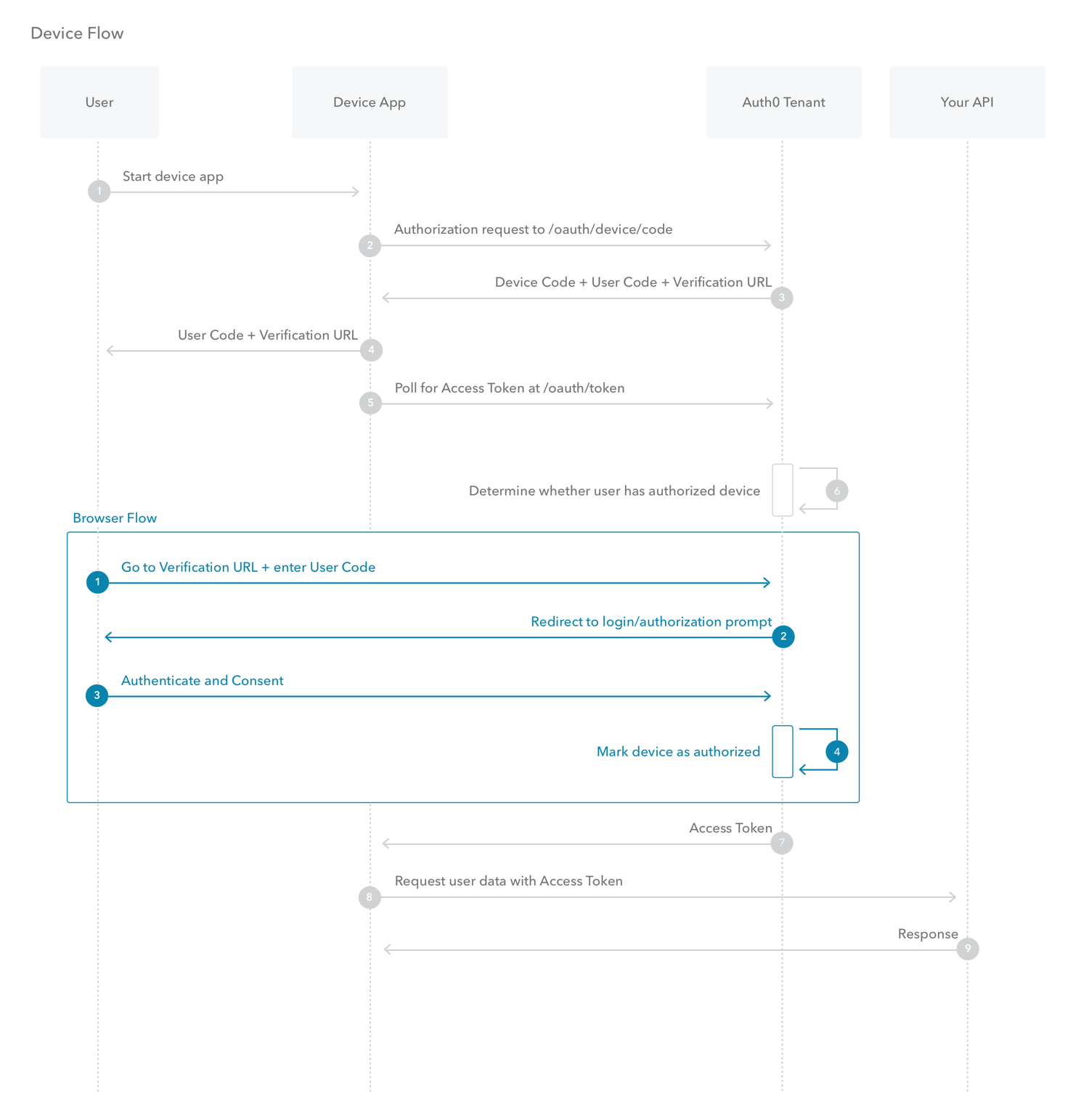

What is Device Authorization Flow?

With input-constrained devices that connect to the internet, rather than authenticate the user directly, the device asks the user to go to a link on their computer or smartphone and authorize the device. This avoids a poor user experience for devices that do not have an easy way to enter text. To do this, device apps use the Device Authorization Flow (ratified in OAuth 2.0), in which they pass along their Client ID to initiate the authorization process and get a token.

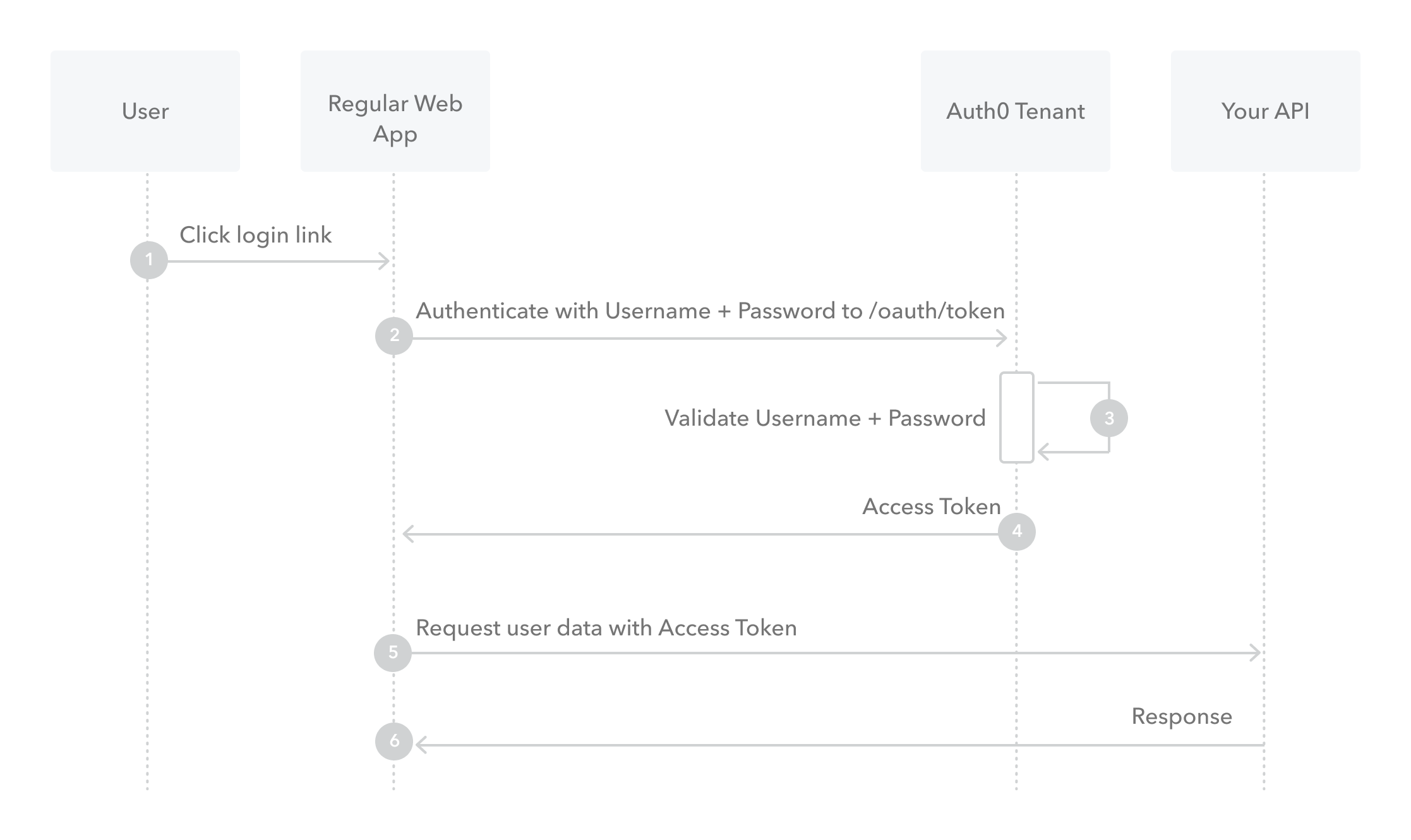

What is Resource Owner Password Flow?

Though we do not recommend it, highly-trusted applications can use the Resource Owner Password Flow, which requests that users provide credentials (username and password), typically using an interactive form. Because credentials are sent to the backend and can be stored for future use before being exchanged for an Access Token, it is imperative that the application is absolutely trusted with this information.

Even if this condition is met, the Resource Owner Password Flow should only be used when redirect-based flows (like the Authorization Code Flow) cannot be used.