reading_notes

Read: 35 - Graphs

Graphs

A graph is a non-linear data structure that can be looked at as a collection of vertices (or nodes) potentially connected by line segments named edges.

Graphs Terminology:

- Vertex - A vertex, also called a “node”, is a data object that can have zero or more adjacent vertices.

- Edge - An edge is a connection between two nodes.

- Neighbor - The neighbors of a node are its adjacent nodes, i.e., are connected via an edge.

- Degree - The degree of a vertex is the number of edges connected to that vertex.

Directed vs Undirected

-

Undirected Graphs

An Undirected Graph is a graph where each edge is undirected or bi-directional. This means that the undirected graph does not move in any direction.

For example, in the graph below, Node C is connected to Node A, Node E and Node B. There are no “directions” given to point to specific vertices. The connection is bi-directional.

-

Vertices/Nodes = {a,b,c,d,e,f}

-

Edges = {(a,c),(a,d),(b,c),(b,f),(c,e),(d,e),(e,f)}

Directed Graphs (Digraph)

A Directed Graph also called a Digraph is a graph where every edge is directed.

Unlike an undirected graph, a Digraph has direction. Each node is directed at another node with a specific requirement of what node should be referenced next.

The Digraph has arrows pointing to specific nodes.

-

Vertices = {a,b,c,d,e,f}

-

Edges = {(a,c),(b,c),(b,f),(c,e),(d,a),(d,e)(e,c)(e,f)}

Complete vs Connected vs Disconnected

There are many different types of graphs. This depends on how connected the graphs are to other node/vertices.

The three different types are completed, connected, and disconnected.

Complete Graphs

A complete graph is when all nodes are connected to all other nodes.

Each vertex is actually connected to every other node on the graph.

Connected

A connected graph is graph that has all of vertices/nodes have at least one edge.

Each node is connected to at least one other node or vertices. A Tree is a form of a connected graph.

Disconnected

A disconnected graph is a graph where some vertices may not have edges. It is possible to have standalone nodes or edges (also known as islands) in a graph data structure.

Acyclic vs Cyclic

In addition to undirected and directed graphs, we also have acyclic and cyclic graphs.

Acyclic Graph

An acyclic graph is a directed graph without cycles.

A cycle is when a node can be traversed through and potentially end up back at itself.

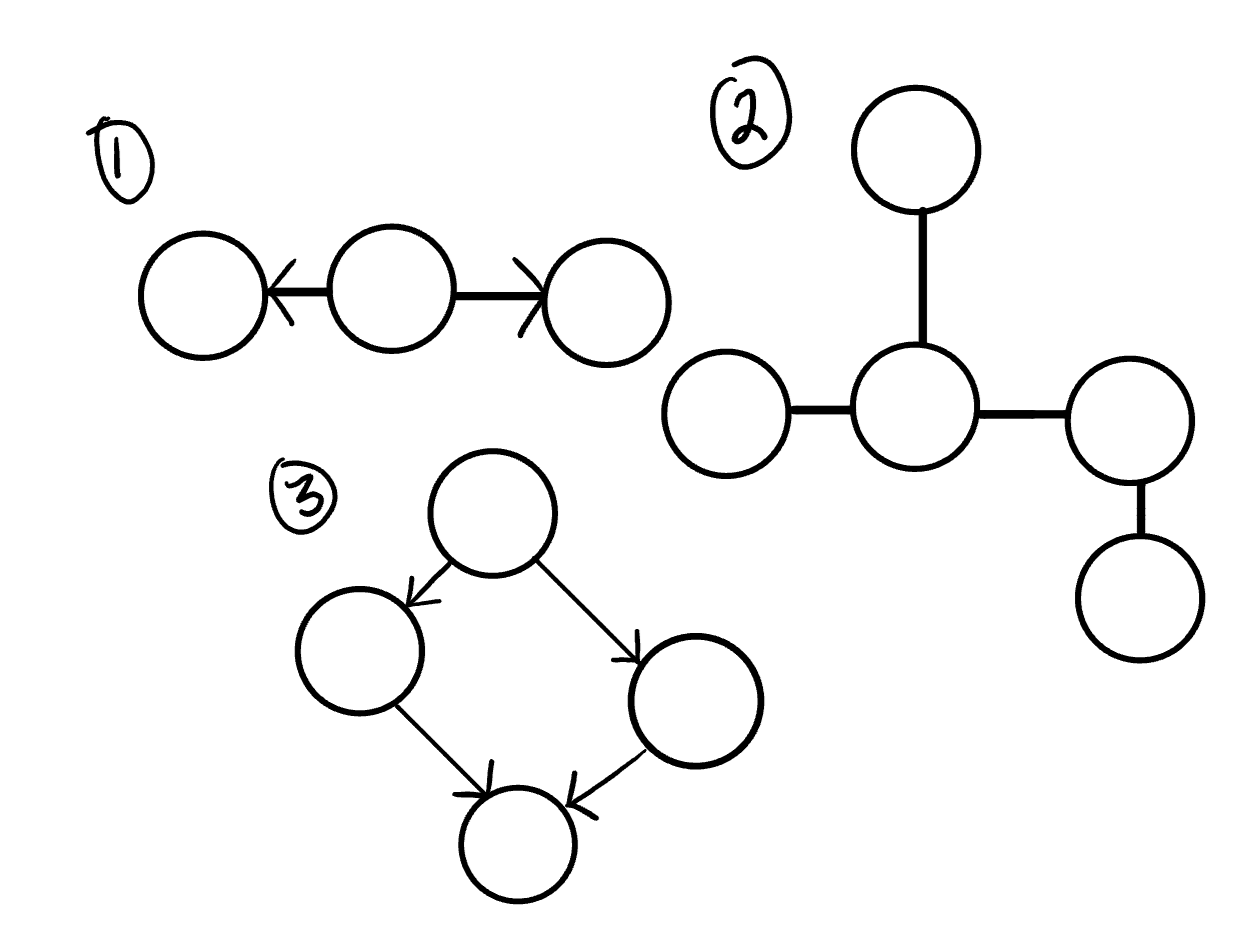

Here is an example of 3 acyclic graphs:

A directed acyclic graph is also called a DAG. This can also be represented as what we know as a tree.

Cyclic Graphs A Cyclic graph is a graph that has cycles.

A cycle is defined as a path of a positive length that starts and ends at the same vertex.

Here is an example of a two different cyclic graph:

Graph Representation

- Adjacency Matrix

- Adjacency List

Adjacency Matrix

An Adjacency matrix is represented through a 2-dimensional array. If there are n vertices, then we are looking at an n x n Boolean matrix

Each Row and column represents each vertex of the data structure. The elements of both the column and the row must add up to 1 if there is an edge that connects the two, or zero if there isn’t a connection.

This is what an adjacency matrix looks like:

- You can see that

Vertex Aconnects to bothVertex DandVertex C. To show this, we place a1in the position of(a,c)and(a,d). - follow this same pattern for the other vertex’s and where they are connected.

- If there is not an edge/connection between the vertex’s, we represent this by placing a 0 in the appropriate point of the matrix. a sparse graph is when there are very few connections. a dense graph is when there are many connections

Within an adjacency matrix, an undirected graph will always be symmetric. This is not the case for a directed graph.

Adjacency List

An adjacency list is the most common way to represent graphs.

An adjacency list is a collection of linked lists or array that lists all of the other vertices that are connected.

Adjacency lists make it easy to view if one vertices connects to another.

This is what an Adjacency List looks like:

Looking at the original graph that we are representing, we can see that Vertex A has an edge to both Vertex C and Vertex D. As a result, we will place both Vertex C and Vertex D in the adjacency list. Just from observation, we can see that we will only place the vertices that are connected in the list. If there is no connection between the vertices, they are not listed.

Thinking about how we will implement this in code? Well, let’s look at what the visual is telling us.

- We can visually see that we are working with a collection of some sort. The visual is depicting a Linked List, but you could easily make it an array of arrays if you’d like.

- Each index or node (depending on the data structure you choose to represent the adjacency list) will be a vertex within the graph.

- Every time you add an edge, you will find the appropriate vertices in the data structure and add it to the appropriate location.

Weighted Graphs

A weighted graph is a graph with numbers assigned to its edges. These numbers are called weights.

When representing a weighted graph in a matrix, you set the element in the 2D array to represent the actual weight between the two paths. If there is not a connection between the two vertices, you can put a 0, although it is known for some people to put the infinity sign instead.

A great way to represent the {vertices, weight} connection is through some sort of key/value pair data structure.

Traversals

You will be required to traverse through a graph. The traversals itself are like those of trees.

Breadth First

In a breadth first traversal, you are starting at a specific vertex/node. This node must be specified when calling the BreadthFirst() method. The breadth-first traversal of a graph is like that of a tree, with the exception that graphs can have cycles. Traversing a graph that has cycles will result in an infinite loop….this is bad. To prevent such behavior, we need to have some way to keep track of whether a vertex has been “visited” before. Upon each visit, we’ll add the previously-unvisited vertex to a visited set, so we know not to visit it again as traversal continues.

As a refresher of what breadth first actually means here it is: Breadth first traversal is when you visit all the nodes that are closest to the root as possible. From there you traverse outwards, level by level, until you have visited all the vertices/nodes.

Here is what the algorithm breadth first traversal looks like:

Enqueuethe declared start node into the Queue.- Create a loop that will run while the node still has nodes present.

Dequeuethe first node from the queue- if the Dequeue‘d node has unvisited child nodes, add the unvisited children to visited set and insert them into the queue.

The visual above shows the levels in which the nodes will be added to the queue. You can see that since the root node is A, it will look the nodes that are only 1 away from the root. This is C,E, & B.

Next it will look at the nodes that are 2 away from the root, this is F, G, & D. It will follow this pattern until it reaches the end of the graph and all nodes have been visited.

Depth First

In a depth first traversal, we approach it a bit different than the way we do when working with a depth first traversal of a tree. Similar to how the breadth-first uses a queue, we are going to use a Stack for our depth-first traversal.

The algorithm for a depth first traversal is as follows:

Pushthe root node into the stack- Start a while loop while the stack is not empty

Peekat the top node in the stack- If the top node has unvisited children, mark the top node as visited, and then

Pushany unvisited children back into the stack. - If the top node does not have any unvisited children,

Popthat node off the stack - repeat until the stack is empty.

- The first thing that we are going to do is look at the root. Following the algorithm we described above, we want to look at all of

Node A’s children (Node BandNode D). SinceNode Bis first, we notice that it has not yet been visited, it then getsPushedinto the stack. - Before looking at the rest of

Node A’s children, we will look at the children ofNode B. and start visiting children that haven’t yet been visited. Node Cthen getsPushedinto the stack.- By the time we hit

Node G, This is the state of our data structure:

- Moving back up the graph, we slowly

Popoff the stack until we reach a child node that has not yet been visited. This just so happens to beNode D, since it is connected toNode B. - The algorithm keeps running and once we hit

NodeE, this is the state of our program:

Notice how Node D has 3 children. We already visited Node E, so we move onto Node H.

Finally, we can see that Node H has a child, so we can wrap up the traversal by visiting Node F.

Node Fgets popped off the stack since it has no children- All three of the children of

Node Dhave been visited so it also getsPop‘d off the stack - Finally,

Node Agets popped off the stack to complete the algorithm.

Real World Uses of Graphs

Graphs are extremely popular when it comes to it’s uses. Here are just a few examples of graphs in use:

- GPS and Mapping

- Driving Directions

- Social Networks

- Airline Traffic

- Netflix uses graphs for suggestions of products

- There is a lot to graphs, and a lot you can do with them. Let this be document be used as an introduction to graphs.

- There is a lot more to them then described, so start exploring, and have fun with them!